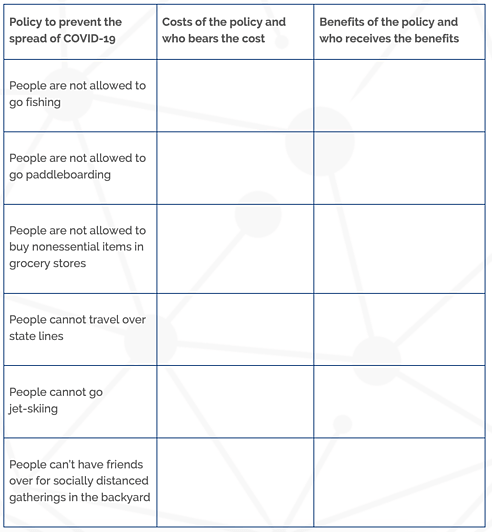

Then there were the huge congressional spending packages. Lots of funding and relief spending was thrown around left, right, and center. But clearly some uses could have a much bigger payoff than others. Although there was great uncertainty over whether we could fund a robust test‐trace‐isolate regime, or a successful vaccine or treatment for COVID-19, the reduction in economic pain that any of these ideas could have delivered was always huge. We knew, too, that vaccines in particular usually take years to roll out, in part because they entail incredibly risky investments in manufacturing capacity specific to the particular vaccine.

Given the potential social benefits of any of these public health innovations compared to the upfront costs, the case for a huge investment in testing, treatment research, and advanced orders for vaccines was extremely strong. Recent research by Tim Johnson, a business professor at the University of Illinois Urbana‐Champaign, and others, has used stock market reactions to vaccine progress to estimate that a vaccine cure that ended this pandemic and its uncertainty would be worth around 5–15 percent of global wealth. The marginal benefits of any measures that encourage economic normalization by speeding up the end of this pandemic by just a few months then would be absolutely enormous, especially relative to the marginal costs of the investment, which were tiny in the grand scheme of things. And yet, as Nobel Prize–winning economist Paul Romer has observed, governments around the world, including in the United States, spent tiny, tiny fractions on medical innovation and testing through this pandemic relative to more direct relief to households and businesses.

And this was despite the fact that all the while the prevalence of the virus was high, the marginal benefit of additional “stimulus” was low in terms of its impact in reviving activity, especially relative to steps that got the virus under control.

—Economics in One Virus, p. 98