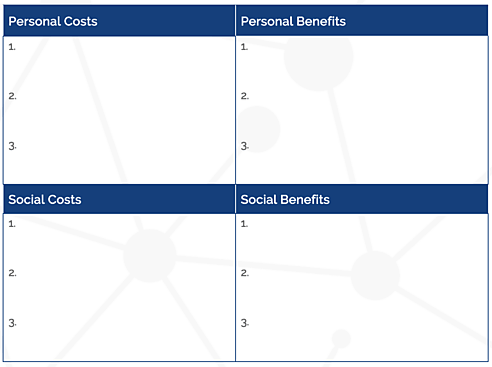

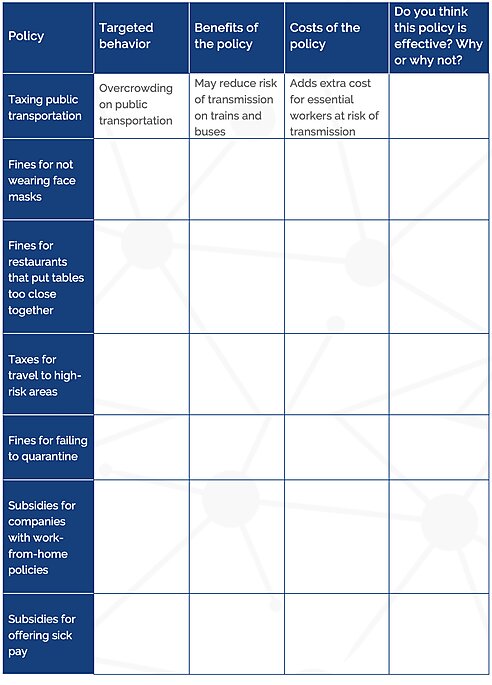

Suppose it was a nice, hot, sunny day here in Washington, DC. The virus was still circulating and there were absolutely no government restrictions on activity. When deciding whether to head for a walk on the National Mall, visiting a few retail stores or a bar en route, I might implicitly think about the costs and benefits to me of my social activity.

Yes, there is a risk I could get infected with the virus by being around and interacting with other people. But compared to other demographic and health groups, my risk of dreadful outcomes from this disease, given that I have no known preexisting conditions, is very low. On the other hand, I would really enjoy getting out for some sunshine, buying some new clothes in a store, and seeing some friends for a drink. I value the benefits of going out highly.

I will try to be respectful of the risks I pose to others, obviously. Yet, I don’t have any major symptoms, except a slightly sore throat that I put down to last night’s whiskey. So, I might feel confident I am not carrying the virus. But the truth is that I do not know whether I’m a carrier, absent an instant test. Perhaps I already picked up the virus from a container from the takeout food I ordered midweek. Or maybe the lady who served me at the grocery store three days ago, or a recent taxi driver, transmitted the virus to me, and I’m in the presymptomatic stage. I cannot know for sure whether I might sneeze or cough or breathe and unwittingly spread the virus while I am in a store or a bar.

If I overwhelmingly worry about the costs and risks to me, perhaps I take insufficient account of the risks of my behavior to others. Again, if I get too close to your grandma in a store while I am not wearing a mask, or else get too close to someone else who might work in her care home or live with her, that means I risk potentially infecting her indirectly without even realizing it. Yet I would not feel the cost of that eventuality, nor is there any feasible way for me to compensate her for my behavior. It probably wouldn’t even cross my mind to consider how I might contribute to hospital congestion or increase risks for workers in crucial industries.

—Economics in One Virus, pp. 21–22