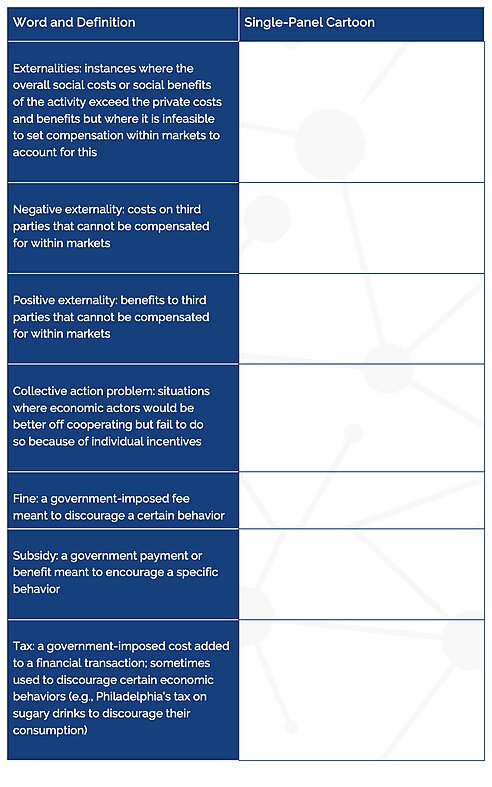

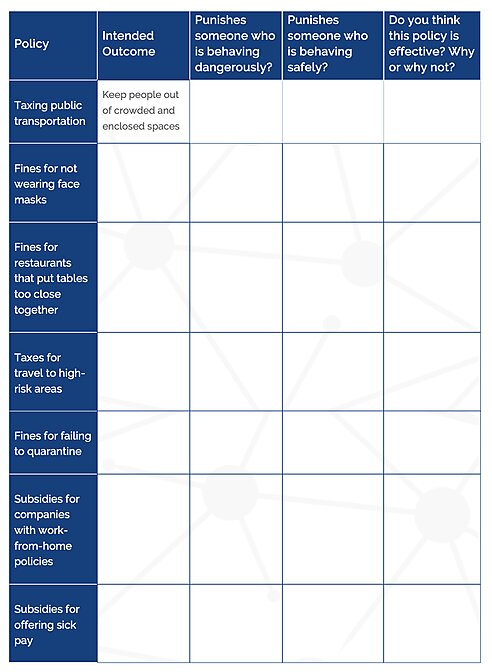

This is perhaps the most extreme example imaginable of what an economist would call an externality. The basic concept is that some purchases we make or some activities we engage in impose costs or provide benefits to other people outside of that transaction for which no appropriate compensation can be paid. For a negative externality, like the activity that propelled the virus into the community in Wuhan, the individuals involved did not face anywhere near the full societal costs of their actions. The implication of a genuine negative externality is that market activity, left alone, may generate too much of the consumption or interaction than is ideal for society overall.

Just like with pollution, the idea here is that when choosing the extent of our social activity, private individuals acting alone will consider their own risks and benefits but take insufficient consideration of the risk of affecting others, not least because they will not know whether they themselves are infected. They will consider the private costs of their actions but take insufficient account of the external costs of their behavior. As a result, too much human interaction will occur relative to what is best for society. The outcome, in economic terms, will be inefficient.

—Economics in One Virus, pp. 18–20